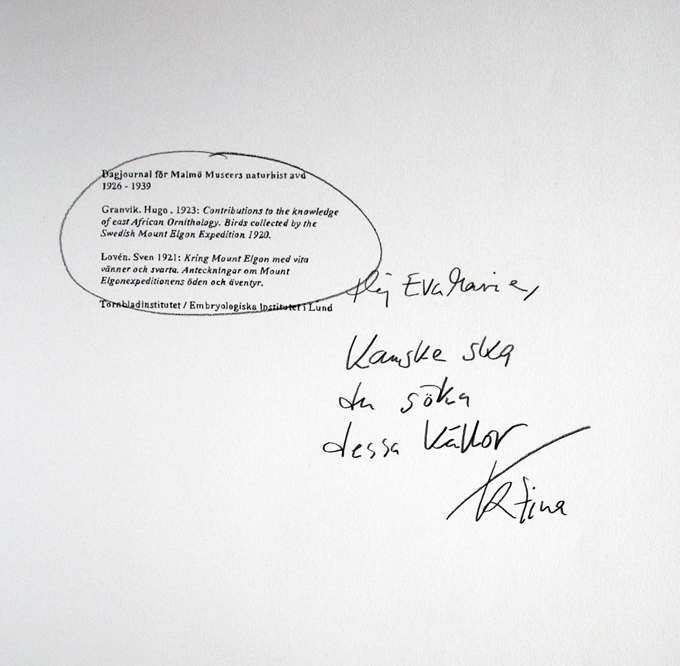

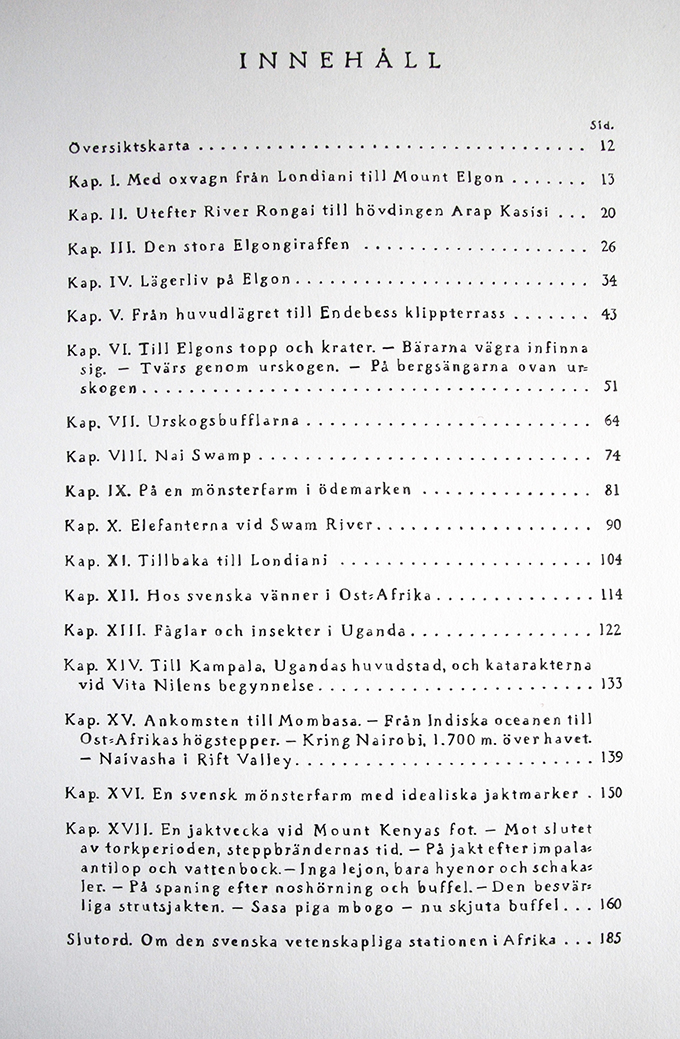

Slit, Scratch, Stuff, Stitch (2015) is an exhibition, and part of the larger project How Do You See?, that emanates from a series of scientific expeditions, which during the 1920s and 1930s went from Sweden to Mount Elgon, a mountain on the border of Kenya and Uganda. Afterwards one of the participants dedicates his notes from the journeys to his children and grandchildren in the hope of waking their interest in animals and nature. But the notes are also about violence. Whiplashes and ear claps are given to both humans and non-human animals in order to push the expedition forward through the difficult terrain. A flock of grazing animals is praised for their beauty and moments later shot to the ground. The goal is to map and categorise, and victims for this effort in the name of knowledge were the thousands of animals that were killed.

Expeditions, such as the one to Mount Elgon, constitute an ambivalent legacy for museums and seats of learning. In the collections one finds stuffed animals and objects that were obtained in a way that is not compatible with how we look at science, ethics or ecology today. At the same time, they are part of the museum’s own history and are still often popular with today’s visitors.

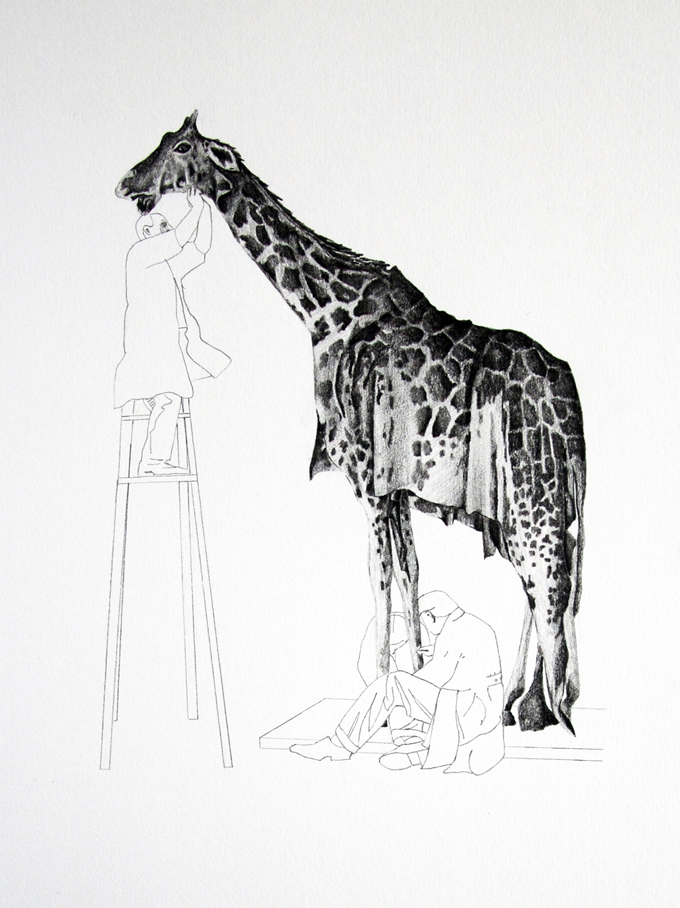

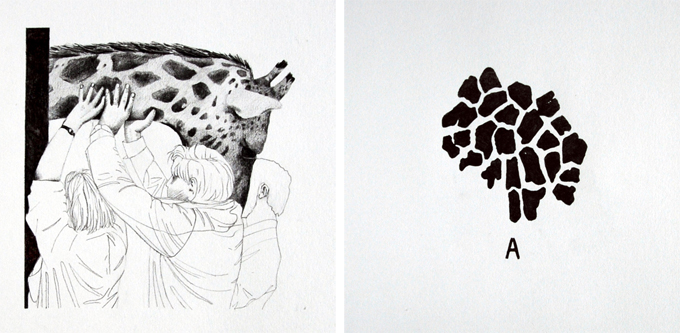

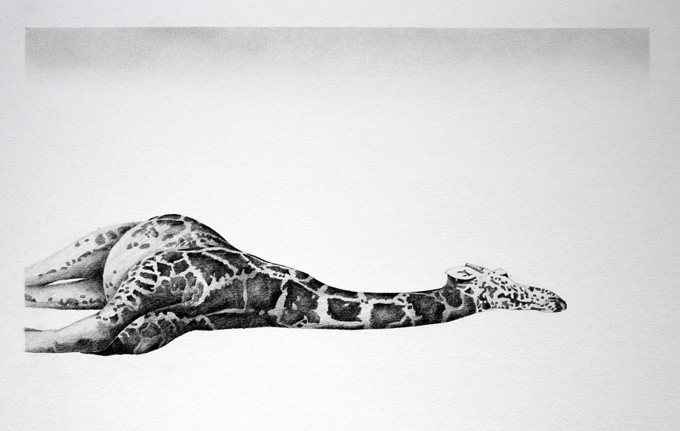

The exhibition is focusing on one of the animals that came to Malmö from Mount Elgon, namely the giraffe that is standing in the entrance of Malmö Museer and which has been looked at by people living in Malmö for over eight decades. Animals that are shown in museums usually consist of a representative of its species, but through the material available from the expeditions the fate of the giraffe is being mapped. In collaboration with Kristina Berggren, curator at Malmö Museum, facts about an individual not only appears in graphite drawings but also appears through texts written by Berggren: She was a pregnant Rotschild giraffe, which lived in a flock together with three other giraffes at Mount Elgon until they were all shot to death within a couple of weeks in the spring of 1930.

The words slit, scratch, stuff, stitch in the title of the exhibition refer to the process of transformation that later takes place. The blood is drawn from the giraffe and it is cut into pieces, the skin is prepared and is then mounted onto a model. Through taxidermy the animal body is built up in order to become an exhibition piece and a representation. The arrangement that the body is presented in and the meaning it is given changes over time, yet the stuffed body remains constant. It is a body that in many ways is in a borderland, between individual and species, between art and science, between the organic and the artificial, between life and death. It is a body whose heart long since have stopped beating, but in its capacity as museum piece most certainly has a long time left to live.

The project How Do You See? consists of three different chapters:

Slit, Scratch, Stuff, Stitch -an exhibition at Galleri S:t Gertrud

We are Reflected in Gazes of Glass -an exhibition at Malmö Castle

Giraffoperiscopic Investigations -a series of workshops at Malmö Castle

C H A P T E R 1

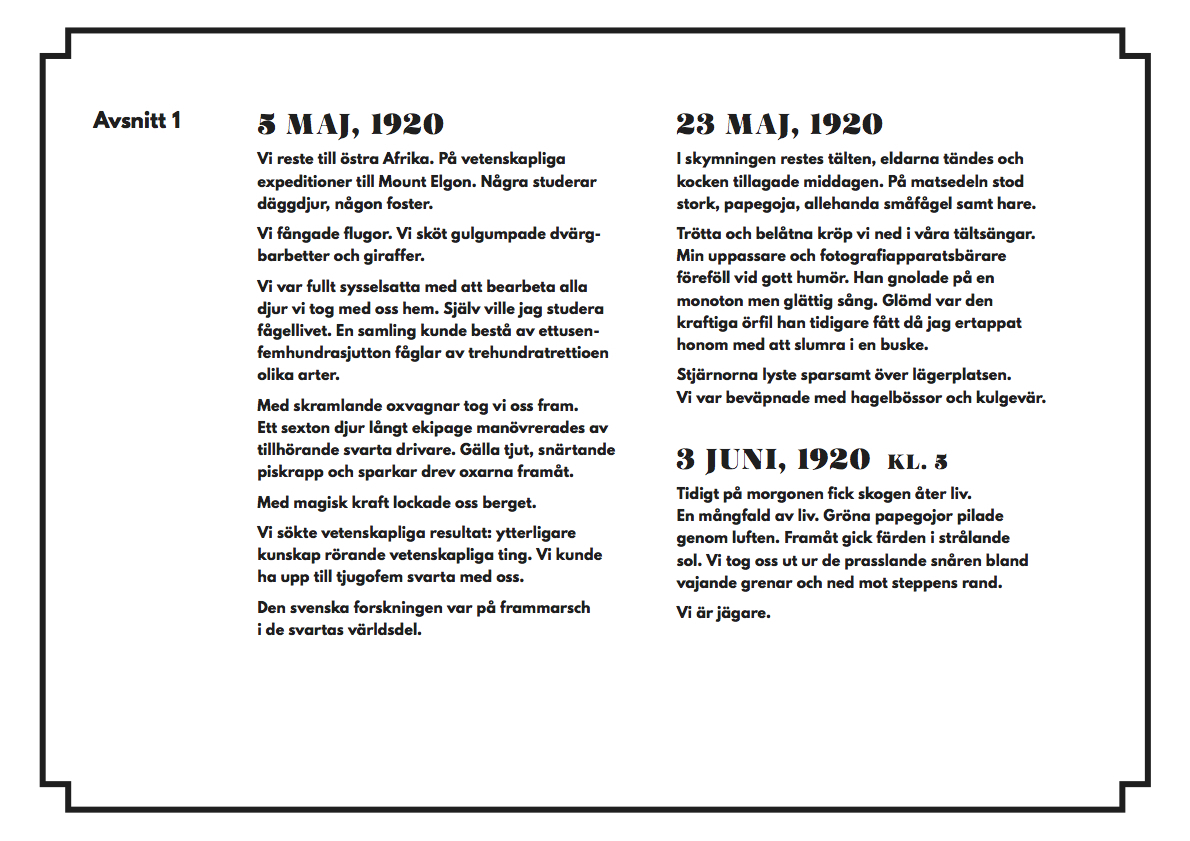

5 MAY, 1920

We traveled to East Africa. On scientific expeditions to Mount Elgon. Some are studying mammals, some fetuses. We caught flies. We shot Yellow-rumped tinkerbirds and giraffes. We were fully occupied with processing all the animals we took with us home. Personally, I wanted to study the bird life. A collection could consist of one thousand five hundred seventeen birds of three hundred thirty-one different species.

We went forward with rattling oxen wagons. A carriage of sixteen animals was operated by the accompaning black drivers. Sharp cries, snapping whips and kicks drove the oxen forward. The mountain attracted us with it’s magical power.

We searched for scientific results: further knowledge regarding scientific matters. We had up to twenty-five blacks with us. Swedish scientific research was on the rise on the blacks’ continent.

23 MAY, 1920

The tents were erected at dusk, bonfires were lit and the chef cooked the dinner. Stork, parrot, all sorts of small birds and hare was on the menu.

We crawled into our camp beds tired and satisfied. My assistant and photography equipment carrier appeared to be in good spirits. He hummed a monotone but cheerful song. The sharp slap he had received earlier when I caught him dozing off in a bush seemed forgotten.

The stars shone faintly over the campsite. We were armed with shotguns and rifles.

3 JUNE, 1920, 5:00 AM

The forest came to life early in the morning. A variety of life. Green parrots darting through the air. The journey went forward in radiant sunshine. We got out of the rustling bushes amongst swaying branches and down towards the brink of the steppe.

We are hunters.

C H A P T E R 2

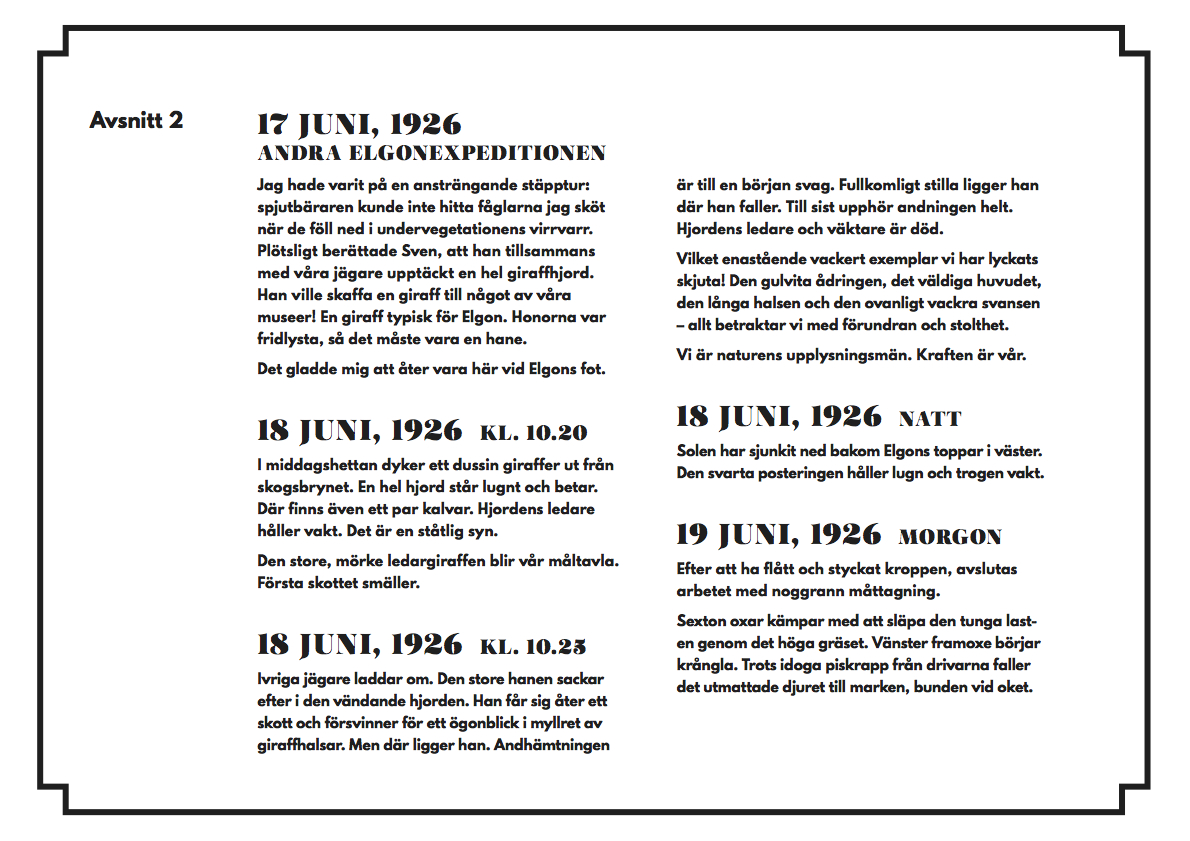

17 JUNE, 1926, THE SECOND ELGON EXPEDITION

I had been on a strenuous excursion to the steppe: the spear carrier could not find the birds I had shot when they fell into the jumble of the undergrowth. Suddenly Sven told me that he together with our hunters had discovered an entire herd of giraffes. He wanted to get a giraffe to one of our museums! A giraffe typical of Elgon. The females were under protection, so it had to be a male.

I was delighted to be back here at the foot of Elgon.

18 JUNE, 1926, 10:20 AM

In the midday heat a dozen giraffes come out of the edge of the woods. An entire herd is quietly grazing. There are also a couple of calves. The leader of the herd is keeping guard. It is an impressive sight.

The big, dark pack leader becomes our target.

The first shot is fired.

18 JUNE, 1926, 10:25 AM

The anxious hunters reload. The great male is falling behind when the herd turns. Once again he is shot and disappears for a moment in the crowd of giraffe necks. But there he lies. His breathing is initially weak. He lies perfectly still where he fell. Finally the breathing ceases completely. The leader and guardian of the herd is dead.

What an amazing and beautiful specimen we have managed to shoot! The yellowish-white veining, the mighty head, the long neck and the unusually beautiful tail -we observe everything with awe and pride.

We are scientists of nature. The power is ours.

18 JUNE, 1926, NIGHTTIME

The sun has sunk behind the western peaks of Elgon. The black picket keeps a calm and loyal guard.

19 JUNE, 1926, MORNING TIME

After the skin is stripped and the body cut into pieces, the work is finished by making careful measurements.

Sixteen oxen are struggling to lug the heavy load through the tall grass. The oxen to the front left is starting to make a fuss. Despite assiduous lashes from the drivers the exhausted animal falls to the ground, tied to the yoke.

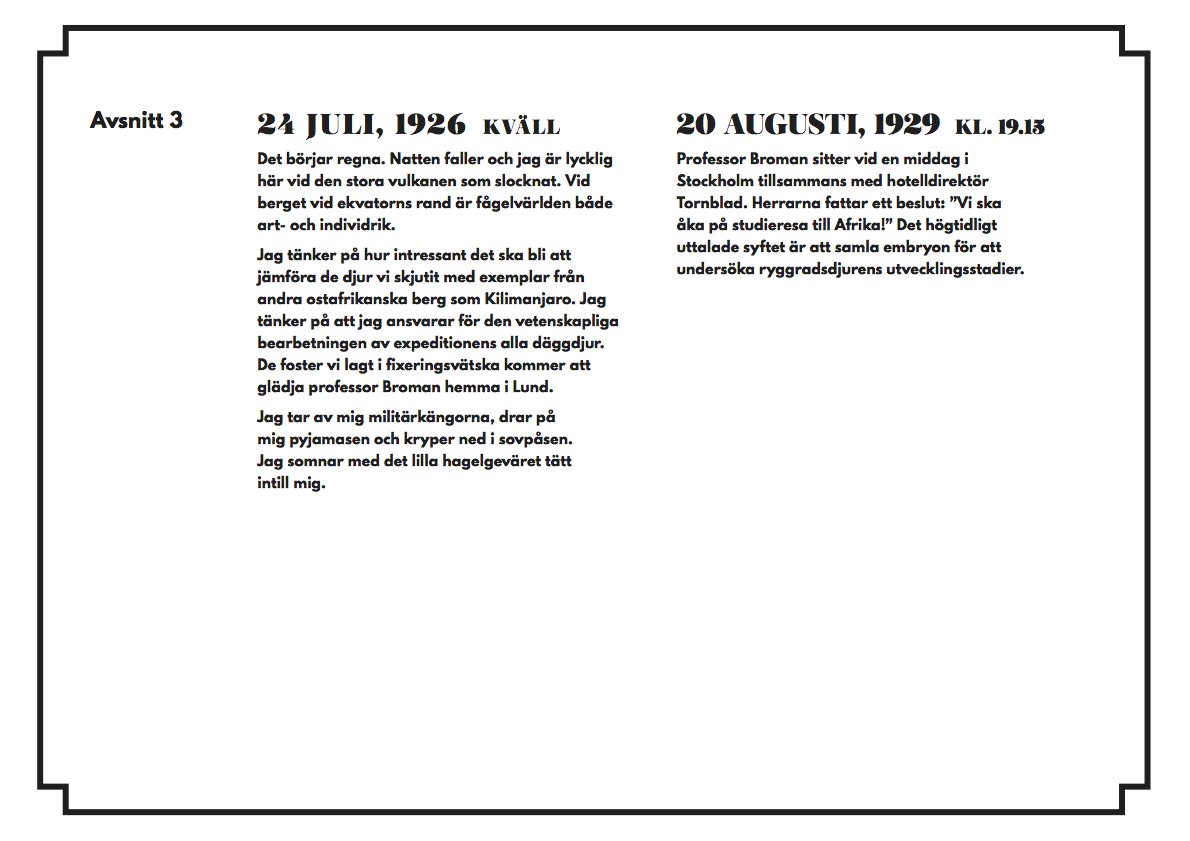

C H A P T E R 3

24 JULY, 1926, EVENING

It starts to rain. Night falls and I am happy here at the great extinct volcano. At the mountain by the brink of the equator the birdlife is great in numbers and species.

I think of how interesting it will be to compare the animals we shot with specimens from other East African mountains like Kilimanjaro. I think of how I am responsible for the scientific processing of all the mammals of the expedition. The fetus we have put in fixative will delight professor Broman back in Lund.

I take off my military boots, put on my pajamas and crawl into the sleeping bag. I fall a sleep with the small shotgun close to my body.

20 AUGUST, 1929, 19:15 PM

Professor Broman is having dinner together with hotel director Tornblad in Stockholm. The gentlemen make a decision: “We are going on a fieldtrip to Africa!” The purpose of the grand declaration is to collect embryos to explore the stages of development of vertebral animals.

C H A P T E R 4

FEBRUARY, 1930, THE THIRD TRIP

The professor needs females for their embryos. After many attempts, he had finally managed to get permission to shoot four specimens, regardless of sex. An English colonel and landowner needed help to push a giraffe herd away from his farm. His cornfields had been trampled.

26 FEBRUARY, 1930, WEDNESDAY, 10:50 AM

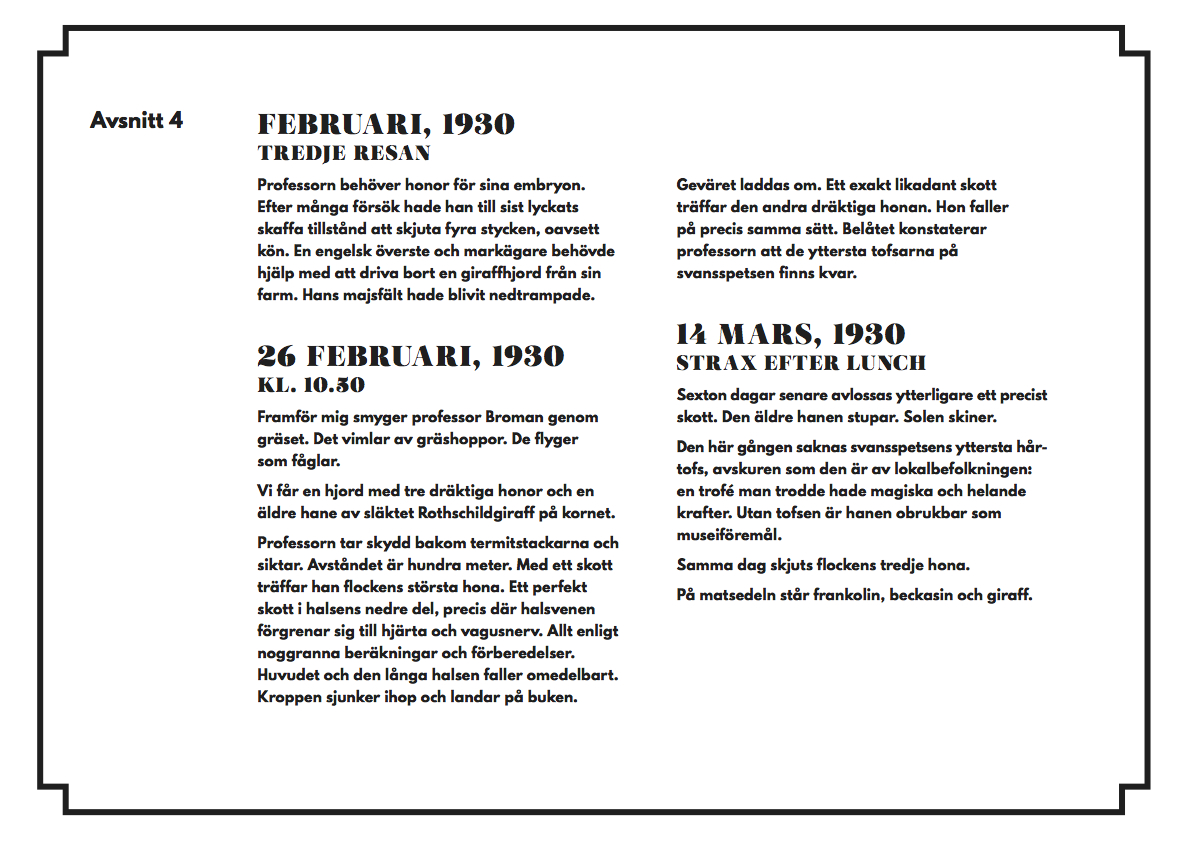

In front of me Professor Broman is sneaking through the grass. Grasshoppers are swarming. They fly like birds. We get a herd of three pregnant females and one older male of the species Rothschild Giraffe in sight.

The professor takes cover behind a stack of termite and takes aim. The distance is one hundred meters. With one shot he hits the largest female of the herd. A perfect shot to the lower part of the neck, just where the jugular vein branches to the heart and vagus nerve. All according to precise calculations and preparations. The head and long neck fall immediately. The body collapses and lands on the abdomen. The rifle is reloaded. Exactly the same kind of shot strikes the second pregnant female. She falls in just the same way. Contentedly the professor states that the outermost tufts on the tip of the tail remains.

14 MARCH, 1930, FRIDAY JUST AFTER LUNCH

Sixteen days later another precise shot is fired. The older male falls. The sun shines.

This time, the tip of the tale is missing its outermost tuft, since it is cut off by the locals: a trophy believed to have magical and healing powers. Without the tuft the male is useless as a museum piece.

The same day the herd’s third female is shot. Francolin, snipe and giraffe is on the menu.

C H A P T E R 5

7 AUGUST, 2015

She stands at Malmö Museum. The first one shot and a prime specimen. Her skin had not been discoloured by a single drop of blood. At the entry hole the bleeding was minimal.

She carried a three-month fetus. His testicles had already come down into the testicular bags. The horns were still in their sacks, and formed two bumps on the skull: 8 millimeters in diameter and 5 millimeters tall.

The skin was transported from Africa to Malmö via Berlin, where it was prepared and tanned.